The Boom Makers

The Munich Code: How the Economic Powerhouse Metropolis Works

manager magazin 2/2026

Crisis? Not in Munich. Driven by old money and new ideas, the Bavarian capital has become a tech metropolis and the pace-setter of the German economy. What's behind the success model? And who?

When Nvidia, the world's most important chip manufacturer, wants to enter the German startup market, it naturally chooses Munich.

A Thursday afternoon in mid-December, it's "Demo Day" at UnternehmerTUM. The founder center of BMW heiress Susanne Klatten (63) was named the best in Europe by the Financial Times, 60 startups are pitching, plenty of interested money has arrived. Asset managers from major families like Hopp, Burda, Herz, or Goldbeck, corporate executives from SAP to Bosch. Around 600 people are buzzing through the halls.

In between stands Nvidia's startup community manager Snehal Deshmukh, a friendly Indian woman in her late 20s, chatting briefly with UnternehmerTUM head Helmut Schönenberger (53). Nvidia, worth around 5 trillion dollars, works with 20,000 startups worldwide, she says. Only in Germany is nothing happening yet. But in February she wants to come back and bring "her boss" with her. "That works well," says Schönenberger casually, presses his business card into her hand and moves on. Nvidia? Nice, but no reason to get excited. The man is used to success.

Schönenberger's protégés have raised around 2 billion euros in venture capital in 2025, a quarter of the amount flowing into startups across Germany. "Everyone always says Europe is sleeping," he calls out in greeting to the packed auditorium. "But we're not sleeping."

Completely Decoupled

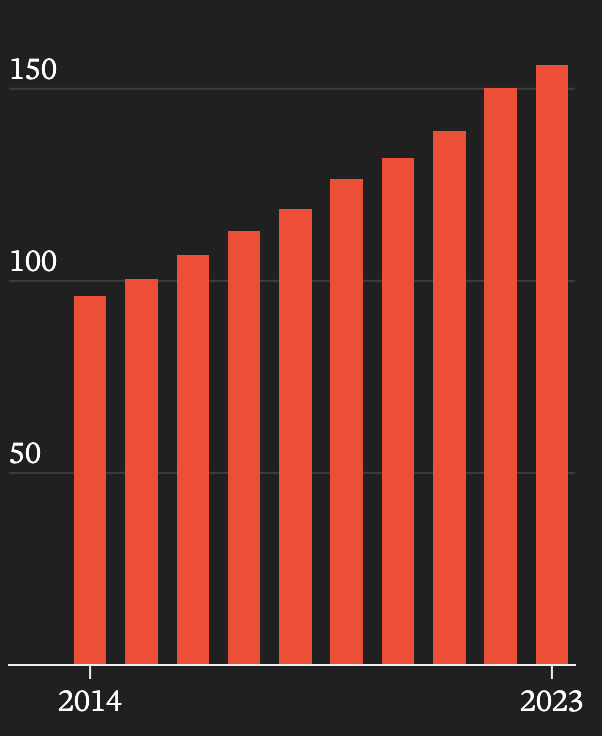

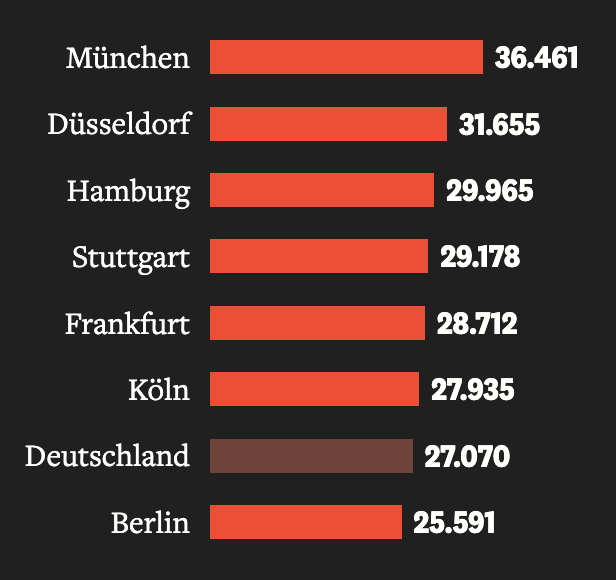

Germany is in crisis – and Munich is booming. The city has completely decoupled: "Above-average GDP per capita, above-average employment, above-average purchasing power," calculates urban economist Simon Krause (31) from the Ifo Institute. A single economic wonderland.

Munich, according to the economist, "set the course early" and developed from a classic industrial location toward high-tech, services, and research. The tech sector in particular is growing above average. Munich, according to Krause's assessment, is likely to "even benefit" from the AI revolution that rather frightens many in the country.

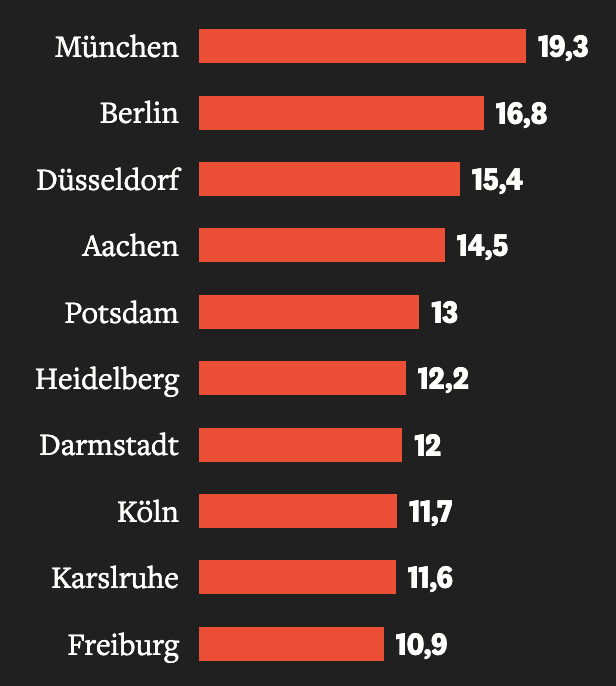

The city produces one billion-dollar startup after another: Helsing, Celonis, Personio, Flix, Scalable Capital, Quantum Systems. Munich has officially overtaken Berlin as the startup capital. The analytics service Dealroom lists Munich as the only German city among the top ten startup hotspots in the world, in a league with Silicon Valley.

Everyone is here: private equity firms, family offices, investment banks – Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and most recently J.P. Morgan opened a branch. The US tech giants Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple have thousands of employees in the city, and OpenAI has its first German office. Google is currently expanding.

While "Fuck-off-Google" activists ruined the search engine's campus plans in Berlin, Munich made the real estate jewel "Postpalast" available and even approved two high-rise towers on the site – on whose roofs Michael Käfer (67), the eternal caterer of the city, is already planning the highest beer garden in the world. Long-time Munich residents are slowly finding it all too much, just like the rents.

In mid-February, the city once again becomes the clubhouse of the global elite. Hundreds of heads of state and top military officials travel with their entourages to the Munich Security Conference (MSC). NGOs, think tanks, and companies from around the world organize countless side events. Venue: the luxury hotel "Bayerischer Hof," which is then bursting at the seams. "In Berlin there would be major protests again," says Christoph Heusgen (70), former German top diplomat and ex-head of the MSC. "In Munich, on the other hand, you feel welcome."

You hear English on every corner today. The young economic elite, many heirs, dominates the city, where you could always be as rich as you wanted without anyone looking. Expensive bags, expensive cars, even the dog leashes are from Bottega Veneta, the flagship stores always a notch more opulent than in other major German cities. All this against a backdrop of classicist aristocratic architecture, golden alleyways, and a snow globe feeling: Everything so beautiful here.

Munich has achieved what the rest of Germany is currently trying in vain: to get moving. The established economic power from DAX corporations like Allianz to Siemens and heavyweight family businesses like Knorr-Bremse helps young techies get started. Old enables new. The city is a constant incubator. Politics, business, society – "everyone," says Ifo economist Krause, "works more closely together here than in many other regions."

Unlike Berlin, where an ecosystem emerged rather accidentally thanks to individual experts, the Munich startup scene is the result of systematic management. But what is the success of the Munich model based on, which many would now love to copy? What – and perhaps more importantly: who – does it take to set the flywheel in motion?

1. Principle Permanent Incubator: Old Money Becomes New

When you meet UnternehmerTUM head Helmut Schönenberger, names fly at you left and right. "Susanne" (Porsche; 73), investor, ex-wife of Wolfgang Porsche (82) and personal mentor to 15 young entrepreneurs, "a truly wonderful woman" whom he will see at the TUM Award dinner at the "Bayerischer Hof" in the evening, along with plenty of other patrons. "Gerhard" (Oswald; 72), SAP supervisory board member, and "Sven" (Smit; 59), longtime chief strategist at McKinsey, are coming the next day. And just now he sat with "Daniel" (Metzler; 33), founder of the rocket startup Isar Aerospace, in an hours-long financing round negotiating about "quite a lot of money."

Schönenberger uses the informal "du" with everyone; for him, rich people are just "people who want to make the world a better place."

The aerospace engineer – suit jacket, backpack, slightly scratchy voice and always enthusiastic – developed the model of a "startup factory" in his master's thesis as a "hyperactive student," as he says. His model was Stanford University with its three pillars: research, corporations, capital. In 2002, together with Susanne Klatten, he docked the founder forge UnternehmerTUM directly to TU Munich. The then university president Wolfgang Herrmann (77) had brought the two together. Schönenberger: "A brilliant matching."

The duo has created one of the largest nuclear reactors in Germany, which continuously generates new things from the fuel rods of old money and produces startups like on an assembly line. Well over 10,000 TU students are channeled through entrepreneurship courses every year, with around 100 startups spun out annually. Around them, the two have accumulated plenty of corporations, customers, suppliers, and investors, from the German money elite to Microsoft mogul Bill Gates (70) or Infosys founder Nandan Nilekani (70). Everything has now proliferated so much that Schönenberger no longer speaks of an ecosystem, but only of "jungle."

There are also other founder centers in Munich: the CDTM, the LMU Entrepreneurship Center, BayStartUP, Werk1. But Klatten's people "beat the drum loudest," as many founders say. It is undisputedly considered the achievement of Germany's richest woman to have set the city's founder boom in motion, not least through her high capital investment. The fourth fund is currently running with 250 million euros.

The melting pot of old and new players is the Munich Urban Colab, which Klatten built four years ago together with the City of Munich in the creative quarter around the corner from the Olympic Park, for 30 million euros. A cube of steel beams, glass, concrete, top-equipped with 3D printer, laser cutter, high-pressure water jet.

On the upper floors, the SAPs, Infineons, and of course BMWs have their people. Below, in the cafeteria, the worlds mix: At the ten-meter-long light wooden tables, students sometimes sit, without knowing it, next to a billionaire. Schönenberger: "No high society behind closed doors, but everything incredibly open." One of his favorite words is "collaboration."

People constantly mingle at fireside chats, lectures, panel discussions, coffee-croissant formats, or final pitches of the startup courses. A Florian Schörghuber (31) from the Munich brewing and construction family conglomerate (Rank 115 on the manager magazin rich list) sometimes attends lectures here and has donated the construction of a workshop hall at the TUM Campus Garching. Fabian (43) and Felix Strüngmann (36) have rented an office directly in the Colab. Their billionaire fathers Thomas and Andreas Strüngmann (75; Hexal, Biontech), besides Klatten the second major patrons, financed the TUM Venture Labs in 2021 with 25 million, which push startups in individual technology fields.

Even Susanne Klatten, who keeps herself out of the public eye as much as possible, can be seen here walking through the corridors and playing the leading lady when necessary; she hosts top events like the annual dinner with 60, 70 CEOs from all over Germany. Klatten has recently been casting her net even wider, drawing family businesses into the startup economy with the Tech Forum.

Socially, the new and the old money have long since merged: When the Frankfurt banking family Metzler invites to dinner at the "Bayerischer Hof" in early December, for example, a highly exclusive event about which nothing at all can be found on social media, Franz von Metzler (39) sits at the table with founders like Daniel Krauss (42; Flix) and Magdalena Oehl (41; TalentRocket), with Trigema co-CEO Bonita Grupp (36) and VW CEO Oliver Blume (57). They chat over game and wine about entrepreneurship in schools and the political situation.

2. "Serious Play" Instead of Eternal Partying Like in Berlin

Munich also owes its rise to becoming the better Berlin to Andreas "Andy" Bruckschlögl (36), Bernd Storm van's Gravesande (50) and Felix Haas (44), the founders of Bits & Pretzels. What started in 2014 as a white sausage breakfast on Sunday mornings at the "Hofbräuhaus," with a few people casually chatting about founder topics, is today the largest network in the innovation scene, with offshoots from Amsterdam to Milan. All of Germany now makes the pilgrimage to the annual get-together. Cleverly timed: during Oktoberfest, when everyone's there anyway.

You meet the three at Werk1, the city's co-working hotspot, on an old Pfanni factory site next to clubs, studios, and a Ferris wheel. They talk in the "Desert Phoneroom," a mini glass box, rented for an hour.

Bits & Pretzels was "helping them help themselves" for the founders back then, to put Munich on the radar as a counterweight to Berlin. They had already founded companies (Ryte, Aboalarm, Amiando) and had their first exit behind them when the masses started founding. And they had the experience that Munich was initially not taken seriously by either investors or developers. "It was necessary to shine the spotlight on the scene," says Haas. They can do that sort of thing: Ex-President Barack Obama (64) they lured as a speaker to the city, US tech giants came in lederhosen. "Such photos go around the world and put Munich on the agenda."

What distinguishes Munich from the startup scene in Berlin? It's not "everyday party" here, says Daniel Krauss, who co-founded Flixbus (2 billion euros in revenue, 5,600 employees) in the city twelve years ago. He is currently driving the largest expansion in the company's history to attack Deutsche Bahn. In Munich, people don't "play around," summarizes Krauss.

Sure, you go to Bits & Pretzels, to Burda's DLD, to Oktoberfest, maybe also to the PIN Party, where once a year those with money, taste, or name meet at the Pinakothek der Moderne. Otherwise, you make targeted appointments. Whoever you want to meet, you call them; "structured meetings," as a multi-hundred-million investor who just moved from Berlin to Munich calls it. Otherwise: The local young entrepreneurs are solid and at home with their families in the evenings. People appreciate a certain bourgeois quality – rather a swear word in Berlin – and well-functioning infrastructure including decent schools.

Scene hangouts like "Klub Kitchen" in Berlin-Mitte, where you constantly meet someone, don't even exist in Munich. To "Käfer" anyway, the headquarters of old Germany Inc., the techies don't really go. At the chic "Brenner" you see and are seen, but whoever visibly tries too hard already doesn't belong.

At most, the venture capital people occasionally invite outside the schedule, "to bring the right people together," says Thomas Oehl (43). He bet on Deep Tech with Vsquared in 2016 as one of the first and invested in today's stars like Isar Aerospace and IQM. With 214 million euros, he leads one of the largest funds in Europe in this area. There's a "quick intro culture," says Oehl. One sentence by email is enough to connect people. "The scene is small, everyone knows the interests at stake." And everyone is busy, time is short.

The pressure is higher than in poor-but-sexy Berlin, higher costs, greater competition for good people. That's why business is always. Whether you go mountain biking or skiing together or sit with the kids at the playground on the weekend. Flix man Krauss has the feeling that "people simply work more in the young Munich startups. Here it's more serious play." Even if, as he admits, it's sometimes all too tidy for him and he misses the "grungy, metropolitan feel" of Berlin.

3. Take and Give: Success Obligates

Wednesday noon, mid-December, Krauss squeezes, rolling suitcase in hand – he has to go to the airport later – into one overcrowded S-Bahn after another, to get from Flix headquarters to Celonis. The software company, founded in Munich and now the most valuable German software company after SAP, could provide the data analysis software for Flix's customer management. 20 people sit around the table, Celonis CEO Bastian Nominacher (41) takes over the presentation himself. A somewhat bizarre situation: One Munich billionaire founder pitches to another – the whole thing in English.

The two have known each other for more than ten years. That's certainly not decisive for the contract, there's no Munich bonus, says Krauss, but: "I know I can rely on them blindly." That's the advantage of the bubble: You know each other well – and that's why you keep investing in the city.

The system thus constantly reinforces itself. While Berlin scene fathers like the Samwer brothers (Rocket Internet) have rather withdrawn (all three now live in Munich), Munich founders give back. Those who have become successful in the city engage with know-how as well as investments. Bits & Pretzels maker Felix Haas, for example, is one of the most active investors and business angels. The stars of the scene regularly come to TU for the "Innovative Companies" lecture, stop by the Colab in the evening, or offer themselves as mentors.

Flixbus founder Krauss sees his "seriousness" thesis confirmed: The young entrepreneurs "live full-blooded entrepreneurship," and that also includes "giving something back as soon as they can."

He himself lives in the countryside near Nuremberg but is in the city four days every other week. He stays at the "Holiday Inn" ("Udo Lindenberg for the poor," he jokes), speaks a lot on panels to students to "create entrepreneurial spirit," or sits in one-to-one mentoring with one high-flyer founder or another (he'd rather not name names, "too private") who are in phases of rapid growth. "I know my way around that," says Krauss.

4. All Inclusive: Munich is for Everyone

20 years ago Munich was "totally cliquey," says venture capitalist Thomas Oehl, "no one from outside could get in." The upper class kept to itself. Today there's "a great openness."

That you can become a somebody from nothing in Munich – hardly anyone has proven this more impressively than self-made man Stefan Vilsmeier (58), founder of the medical technology company Brainlab. Vilsmeier, son of a salesman from Poing, a small town east of Munich, his mother a housewife, has made it into Munich's best circles.

And embodies startup "culture" in the best Munich sense: Vilsmeier sits on the university council of TU and in the Academy of Fine Arts, is in the Premium Circle of the State Opera, main sponsor of the "Ja, Mai" avant-garde festival, and since 2024 even chairman of the Society for the Promotion of the Munich Opera Festival, fortress of the established society.

Vilsmeier is one of the first overachiever nerds of the republic. At 15, he taught himself programming; at 19, he developed software-supported navigation systems for brain and spine operations and founded Brainlab. That was 1989, when as a founder, as he says, you were still "looked at sideways." At the IPO, which was canceled last summer due to the poor market environment, a valuation of 2 billion euros was on the table.

Vilsmeier is a serious person who barely cracks a smile in conversation. He sees entrepreneurship as a "creative, almost artistic process," his company as a "Gesamtkunstwerk" (total work of art): His Brainlab headquarters at the tower of the old airport in Riem is now also a cultural venue: His art collection hangs on the third and fourth floors. The atrium is a concert hall. Five stories high, everything in white, soft light, just 300 seats, and above all: "perfect acoustics," states the host. Every few weeks he brings the top stars of the State Opera for performances.

December 13, 7:30 PM, Vilsmeier's Christmas concert, now one of the social highlights of the city. Vilsmeier greets one or another, a kiss on the right, a kiss on the left. People wave to each other across the hall, they know each other. The atmosphere: almost private. The musicians sit in the audience, stand here and there, a house concert XXL.

Afterwards, a select group of 50, 60 people goes up to the lounge under the glass dome in the tower, chatting over tuna tataki canapés and risotto, the artists stop by. Vilsmeier's circle includes Bavaria's Science Minister Markus Blume (50), DLD grande dame Steffi Czerny (71) and management consultant Roland Berger (88) including his wife, with whom he sometimes discusses over dinner how to further promote the city's culture. Vilsmeier considers the cultural environment "crucial for attracting top talent."

Engagement as an entry ticket – the new Munich is for everyone. Everyone can participate, if they want. You don't need ten years "to become part of it here. Ten hours are enough," says UnternehmerTUM creator Schönenberger. There are so many "touchpoints," you can start immediately.

Whoever comes to the city is immediately fed into the machinery. Wieland Holfelder (60), Google's representative in Munich, is a partner at TUM and sometimes brings people from the corporate headquarters in Mountain View, like recently "Astro" (Teller; 55), CEO of future forge Google X.

When Christian Haub (61) or Max Viessmann (36) settle their investment crews in Munich, they immediately have dozens of invitations on the table. Tengelmann CEO Haub supports the TU project Circular Republic, Viessmann has been financing a new field for climate-relevant business models at the TUM Venture Labs with a seven-figure sum since October. He considers the city "one of the most vibrant ecosystems in Europe for Deep Tech." Unlike Berlin, he sees "things designed for greater longevity." The founders here have "a serious interest in making a substantial positive impact."

5. "Ursula" and "Armgard": Politics Joins In

"You can say what you want about Söder, but..." is the typical sentence starter of many founders when it comes to politics. For his space plans in Oberpfaffenhofen, Markus Söder (59; CSU) was ridiculed as megalomaniacal when he took office as Minister President in 2018. Now a defense and space cluster with many startups is emerging there.

Investors like Viessmann see the "long-term agenda" of Bavarian state politics as "pacemakers for success," entrepreneurs like car rental executive Alexander Sixt (46) the close interplay between business and politics: "No ideology is cultivated, but cooperation. Decisions are made pragmatically, not doctrinally." Federal politics, Sixt thinks, could learn from this.

Munich's SPD mayor Dieter Reiter (67) already pushed the ecosystem as economic commissioner and makes no secret of regularly meeting with the heads of the largest corporations for "economic summits," to hear "where we can support." He sometimes "can't do much with" the politics of his comrades in Berlin. For him, it's first about the welfare of the city.

City, state, Chamber of Commerce, founder centers – all the players constantly sit together in rounds. A kind of steering committee is Munich Innovation Ecosystem GmbH with its "Innovation Agenda 2030": Munich is to become the leading AI and startup stronghold in Europe. 5.5 billion euros the state is putting into its high-tech agenda: 1,000 new professorships, 13,000 student places, laboratories and infrastructure.

Big words, lots of money – but also micromanagement: In the Colab of UnternehmerTUM sits "Ursula" (Triebswetter; 58), municipal authorized signatory, who sees herself as a "door opener into the administration": Getting a visa for a founder, attaching sensors at an intersection for a startup's measurement series – she always knows who to call. "Scrubbing away problems," is what UnternehmerTUM head Schönenberger calls it.

Recently he's been doing this in Berlin too. He has meanwhile become a kind of startup guru of the republic. During a visit to the Colab, he had convinced the former Federal Economics Minister Robert Habeck (56; Greens) to set up ten more "startup factories" throughout Germany following the Munich model. They started in October 2025, from Hamburg to Essen. Schönenberger now sits on the coordination committee of the Economics Ministry – and works with "Armgard" (Wippler; sub-department head) on nationwide bureaucracy reduction ("Startup in a day") and more startup-friendly tendering procedures.

Whether the Munich Code can be transferred to other regions – for economist Simon Krause, that's the "one-million-dollar question." Helmut Schönenberger sees the chances at 50:50. But undaunted as he is, he says: "We need people who are really passionate about it and really put in 20, 30 years. You just have to start somewhere."